Roberto Salas, Photographer Who Portrayed The Epic Cuban Revolution.

When you enter Roberto Salas Merino's house, you are dazzled by the quantity – and quality – of the photographs that occupy each wall. Fragments of his series: Nudes (1994-2004), Así son los Cubanos (2007-2015), Nostalgias (2009-2019)… But also, of course, a space reserved for his most beloved images: those that portray the revolutionary epic.

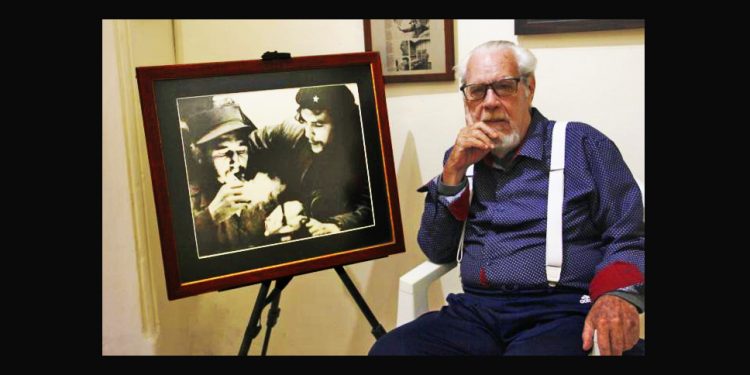

There is The Lady and the Flag (1957), that photo where a July 26 flag flies on the Statue of Liberty. And January, 1959, where Fidel and Che share a moment that he himself considers his masterpiece.

How many snapshots have you taken in your entire life? Salitas – as his colleagues call him – laughs when thinking about the amount. And so he receives Granma in the living room of his home, which summarizes six decades of work, as a result of recently being awarded the 2025 National Prize for Plastic Arts.

AN INHERITED PASSION

Photography came to him by inheritance and by destiny. His father, Osvaldo Salas (1914-1992), was one of the great names of Cuban epic photography, along with Alberto Korda, Raúl Corrales, Ernesto Fernández and Liborio Noval. He had emigrated to the United States in 1926, looking for better horizons, and there, in New York, Roberto was born in 1940.

At that time, Osvaldo became involved in the visual arts and, between 1950 and 1958, he consolidated his prestige as a photographer, opening his own studio in front of Madison Square Garden, one of the most important sports and entertainment complexes in the city.

It could be said, then, that we are talking about an inherited passion: «It was in steps. I was in high school but I had to help him in his business: photos for weddings, baptisms, birthdays... I grew up among chemicals, developing and printing images.

At just 16 years old, a photograph of him would become the most important of the revolutionary movement taken outside of Cuba. It was The Lady and the Flag: «That day my partners climbed to the crown of the statue and placed the flag. I managed to capture the image and they picked it up quickly. I think I was tremendously lucky –he says–, you know how the press is: sometimes there are dead days, without important news. Thus it was published in four of the seven newspapers in the city and in agencies throughout the country. Even Life magazine published it!

Days later, some Puerto Ricans tried to repeat the feat with their own flag, but found the windows sealed. “Apparently I had something to do with it,” he smiles.

PHOTOGRAPHER AND FRIEND OF FIDEL

In 1955, Fidel Castro came to New York to raise funds for the struggle. He needed to reproduce images of Batista's crimes and came to the Salas studio. The job cost ten dollars, but when Salitas took him, Fidel had no money.

«I remember we were in a kitchen. He and other fighters counted the money raised for the cause. And to me, at 15 years old, it occurs to me to say: “How are you going to tell me that you don't have money, with everything that's on the table?” It was the first time I heard a speech: “That money is sacred, it is for the struggle..., I can't touch it, it doesn't belong to me.”

«That didn't stop there. In 1961, after an event in Matanzas, a former guerrilla approached Fidel to ask for a job. He finally got it, but he also took the opportunity to ask for money.

«Fidel approached us, to see if we could lend him something. Like everyone else, I put my hands in my pocket, but he stopped me and said, “Not you, I still owe you ten dollars.” End of story, I'm still waiting for my money.

That incident, which began in New York, was the seed of a lasting friendship. On January 2, 1959, Salitas took the opportunity to travel to Cuba and document the revolutionary epic. Then he coincided with Fidel, when he returned in the Freedom Caravan. Since then, Osvaldo became the head of the Photography Department at the Revolución newspaper and Roberto was one of his personal photographers.

His favorite photograph dates from that time: January, 1959. «For the first time I saw Che. I was sitting with Fidel in the Presidential Palace. The lighting was very poor; I had to use the match when they lit a cigar, but since it was of poor quality, they did it several times. Forget everything else – he points to the image next to him – that's the best thing I've ever done. “It was very easy to work with Fidel, he always respected our work.”

GRANMA, VIETNAM, AND ITS ONLY PHOBIA

Salitas is considered the founder of the Granma newspaper, established after the merger of Revolución and Hoy. He collaborated for years with the Photography Department, and even published some texts. But he never received a fixed salary: “I preferred it that way. “I had the door half open to decide what things were best for me.”

His wife, Lourdes Socarrás, intervenes in the conversation to specify dates and tell anecdotes. It was she who remembered how Roberto asked Celia Sánchez for permission to travel to Vietnam, where he worked between 1966 and 1973.

He treasures memorable events from that country, such as being among the few Cubans who shared with Ho Chi Minh, whom he remembers as a very simple and humble man. Other, sadder moments taught him that war does not distinguish between people.

«On the border, underground, lived a little girl named Mai. He became attached to me in a few days because his father had died. When I returned to Hanoi, I sent a doll to a colleague who was going there. Two weeks later, he came to see me and, without saying a word, returned the doll to me. To this day it saddens me.”

As a war correspondent, he faced many fears. But Lourdes reveals that her only real phobia is of closed spaces, originating in an experience in the Matahambre Mines, which she photographed for Granma in 1968. “I spent a good time there, not only underground, where copper was extracted, but also on the surface, capturing how the miners lived.”

When revisiting the press in those first years of the Revolution, the preponderance of images over text, almost non-existent, is evident: “A large part of the population was illiterate, so the writings were brief, the expressive power of photographs was prioritized, there was no better way to communicate.”

In subsequent years, in addition to the photographic series mentioned at the beginning, others such as Yagrumas, Tabaco, Epigramas, and an essay on the last departure of the Cabildo de Regla stand out. At the same time, he has held various exhibitions and his books have been published both in Cuba and abroad.

A UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE

«Photography is a way of speaking, of reaching people you don't know or don't know how to read. The images are universal. This is how he thinks about the usefulness of this art and considers that “the most important thing is that the award pays tribute to the entire union, not to me. I may be a fashionable author, pure coincidence, but it should have been given long before to colleagues who also deserved it.

Regarding Cuba, he assures that here he found what he did not have in New York: a home. «My father was always very Cuban and wanted to return. Americans are shit, the immigrant will always be an immigrant. Thanks to this Island I was able to become a photographer.

Today, at 85 years old – almost four years without taking new photos – he reads, writes and cooks from time to time. Nor does he conceive of other projects: «I could have done some things better, but that doesn't worry me now. I am satisfied with everything I did. At least I'm leaving something for tomorrow. “That's what's important.”

And as he finishes, his gaze scans the walls full of images, perhaps few that fail to do enough justice to so many years of work, but that reveal pieces of stories that he, with his camera, gave us forever.